A Conversation with Composer Fred Onovwerosuoke

On Classical Music, Race, and A Triptych of American Voices: A Cantata of the People

by Yoshi Campbell

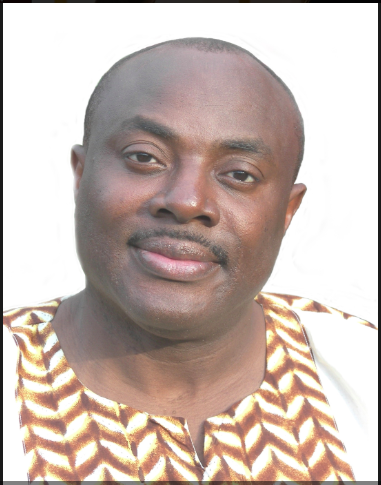

"FredO," as friends call him, has done field research in more than thirty African countries, the American Deep South, the Caribbean, and South America for what he likes to call “traceable musical Africanisms.” In 1994 he founded the St. Louis African Chorus to help nurture African choral music as a mainstream repertoire for performance and education. Today, the organization's mission has broadened to include classical/art music by lesser-known composers, particularly of African descent, and has been renamed the Intercultural Music Initiative.

Fred Onovwerosuoke’s new work, A Triptych of American Voices: A Cantata of the People, was commissioned for Coro Allegro, Boston’s LGBTQ+ and allied classical chorus, Artistic Director David Hodgkins and pianist Darryl Hollister by chorus member Willis Emmons and his husband Zach Durant-Emmons.

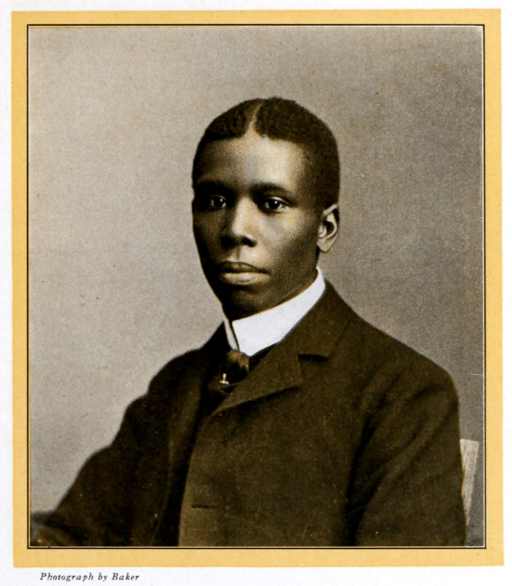

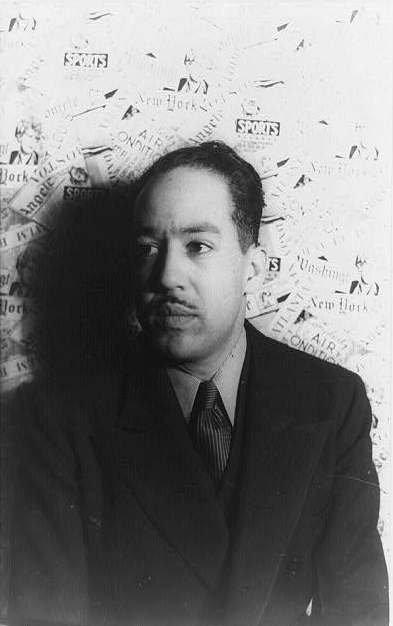

Onovwerosuoke describes it as "a kaleidoscope on prevailing themes of American political discourse, from the purview of an immigrant composer,“ told from the prisms of three great poems - "Sympathy” (I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings) by Paul Laurence Dunbar, "As I Grew Older" by Langston Hughes, and "We Need to Talk" by Michael Castro, the late Poet Laureate of St. Louis.

Don't miss the world premiere, Sunday, March 24, at 3pm, as Coro Allegro presents America/We Need to Talk, at Harvard University’s Sanders Theatre. Visit coroallegro.org for tickets and for more information.

If every concert hall in America could allow a wide variety of repertoire to come in, could allow a different palette of music to be heard, with influences from the East and the Middle East, from Africa, the Caribbean and Latin America, influences from the wealth of experiences shared by diverse immigrant populations to America -- that would be “classical music reimagined.” Audience sizes will increase, not decrease as the recent trend seems to indicate.

Yoshi Campbell: A reviewer once described your music as “classical music reimagined.” I’ve been working on issues of diversity, inclusion, and equity in classical music, so I want to begin by asking for your thoughts about this. Do you see your work as reimagining what we think of as classical music and if so, how?

Fred Onovwerosuoke: “The term classical music is just an umbrella term for music that is disciplined and well thought-out; music whose structures can convey imagery, stories, a variety of human emotions, sensibilities, etc. The ability or the capacity to express multitudinous ideas in music is not an artistic vocation exclusive only to European Americans. It is an innate capacity in anyone with the requisite talents, training and skill-set, irrespective of their racial or ethnic background.

True, the concept of ‘classical music,’ as the term implies, was first formalized in Europe. But how people traditionally have been able to tell these musical narratives is through the songs from their own neighborhoods, the chants of their communities, and a wide spectrum of musical experiences. Every classical music composer should be able to convey ideas through their own cultural narratives and their own experiences, not just through the lens of European culture, or within the confines of the acceptable music conservatory canon.

If every concert hall in America could allow a wide variety of repertoire to come in, could allow a different palette of music to be heard, with influences from the East and the Middle East, from Africa, the Caribbean and Latin America, influences from the wealth of experiences shared by diverse immigrant populations to America -- that would be “classical music reimagined.” Audience sizes will increase, not decrease as the recent trend seems to indicate.

Yoshi: So what differentiates music as "classical" is not what period it was written in or what culture it emerges from but a question of form.

FredO: Yes, popular music is also an art. But the key word is ‘popular.’ Whether it is country, rap, trap, raga, reggaeton, fusion, soca, etc. it doesn’t matter what genre, the formula for most popular music is usually predictable. You have verse, verse, bridge, ending. It’s supposed to be simple, catchy, with gripping tunes that can easily connect with people.

Classical music is a different kind of art - supreme art music, if you will. It is music that is intuitive, like a great painting, sculpture, or piece of architectural wonder. It is the only medium through which a composer can tell a story, stretch the listener’s imagination, make the listener visualize drawn out tonal through microtonal colors. Classical music has that unique metaphysical leverage to tug at a wide range of human emotions. It is not summarily consumable or readily functional; it’s purpose is to reach deeply and draw out a whole lot more from one’s sensibilities and entire being.

In the days of Bach, Handel, Mozart, Brahms, Haydn, tonal composers, lyrical composers, they always had a tradition of borrowing from popular music, always including something the audience could take home and whistle. That was a trick they used in the age of tonal music; many composers fashioned portions of musical vignettes or what I like to call “singable takeaways” that would stick on the minds of their audiences. So there was a tradition of borrowing or re-appropriation from communal music. This convention has persisted even in the atonal, multi-tonal and microtonal music championed from the era of Debussy, Hindemith, Ives to contemporary composers.

The entire work is designed as a partnership of voices and musicians sharing aspects of one grand song. It is a commentary on the contemporary American political climate, of a people seemingly entrapped in ongoing, unrelenting and partisan tribal political discourse, of a people who indeed “know why the caged bird sings.”

Yoshi: Let’s talk about the work you have written for Coro Allegro and pianist Darryl Hollister, A Triptych of American Voices: A Cantata of the People. Why did you call the work a “Triptych of American Voices”? I note the libretto draws on more than three great American poems, three voices, quoting sources as diverse as George Orwell and Vondou ritual.

FredO: I embarked on creating a grand work in three movements, each of which is starkly unique in form and style, hence the word “Triptych.” With three great American poems in hand, I set out to compose a grand musical treatise in three parts, subdivided into nine sections – Prologue, Indigenes & Immigrants, Fiesta, Why the Caged Bird Sings, We The People, As I Grew Older, Responsorials, Heed the Gentle Voices, and We Need To Talk - each section helping to forge one contiguous musical narrative. I’ve used ancient African oracles of the ‘Vondou’ priestesses and the George Orwell quote as lead-ins into or moments of pause, or intersection between the three parts, as reflections.

Yoshi: What about the subtitle: “A Cantata of the People”?

FredO: “Cantata” comes from singing. “A Cantata of the People" is when the people express themselves through song – songs of protest. In this work, a people who have been stifled are telling their story through song and instruments.

The entire work is designed as a partnership of voices and musicians sharing aspects of one grand song. It is a commentary on the contemporary American political climate, of a people seemingly entrapped in ongoing, unrelenting and partisan tribal political discourse, of a people who indeed “know why the caged bird sings.” You can hear it right from the leitmotif first uttered by the flute in the overture.

Yoshi: The beautiful bird call that opens the work?

FredO: That simple bird call ‘nagged’ me for almost a whole year before I eventually wrote it down. The rest of the work began to take form from there. In the introduction to Dunbar’s poem of the caged bird, I wanted first to offer a brief narrative on the origins of our United States of America, hence the “Indigenes and Immigrants” and “Fiesta” subsections, in which you can hear the influences of Native American dances, Pow Wows, and Fiesta. I also drew on experiences and ideas from my music workshops in North Carolina, a women’s chorus in Brattleboro, Village Harmony workshops across New England, and more, to create a tapestry of some sorts. But it all begins with a simple bird-call. The ensuing responses emerge from melodic material that is needful, deliberate and varied, with harmonic treatment that is familiar, exotic, atonal, incidentally dissonant, but sonically and esthetically relevant.

Yoshi: Part II begins with a quote attributed to Orwell. “A people that elect corrupt politicians, - impostors, traitors, thieves, - are not victims, they are accomplices." Why quote Orwell in an American Triptych?

FredO: In part, for the same reason George Orwell’s “Animal Farm” and “1984” are recommended reading across many schools in the United States. And mind you, America is supposed to be an amalgam of cultures and immigrants with diverse experiences, so in a way I thought the quote was particularly significant commentary on this moment in American history; a jab, if you will, on the 2016 Election. I wanted to say we are complicit; that we are part of this; that we helped create the mess we are in. And what better way to say it than use the Orwell’s quote in a chant during a protest march. Metaphorically, of course.

Yoshi: Let’s talk about the amazing Langston Hughes poem, “As I Grew Older,” that follows in Part II. It has powerful images of a wall rising up between the speaker and his dream that seem so relevant to the debates America is having right now. Was that why you chose it?

FredO: The wall in Langston Hughes poem speaks to Black Lives Matters and to the Wall our President Trump is clamoring to build on our southern U.S. Border. But beyond the Wall, what Langston Hughes was talking about is a race thing, an ethnicity thing, a sexuality thing, a trans, an accent thing, a gender thing, an ‘other’ thing.

Someone who has the financial means to build a wall, or lord their prejudices on others can build a wall to prevent you from obtaining your dreams. History reminds us that the leaders who built walls in the past were all autocrats, tyrants and brutal dictators– the Berlin Wall mandated by Nikita S. Khrushchev in 1961, the Great Wall of China mandated by various Chinese emperors from about 220 BC, just to mention two most notable walls.

In the first poem by Paul Laurence Dunbar (the poem later paraphrased by Dr. Maya Angelou), the caged bird would rather be out smelling the flowers, like other free birds, but instead he is locked up in a cage, his wings bruised and bloodied from his futile attempts to be free. We seem to perpetuate age long oppressive policies that put our own people in cages. We see people with different cultural or socioeconomic experiences, label them as ‘the other’ and then build walls to keep them out of our vicinities.

Yoshi: I noticed that while your setting of Dunbar stays close to the ideas of the poem -- you can hear the bird singing, straining to be free, etc. -- in your setting of the Hughes, and the piano interlude that sets it up, there is a playfulness that recalls jazz or Gershwin, or Ellington, that almost belies the poem’s themes. You even note somewhere in the score that there should be “a little swag on the piano” and yet there is such darkness of the poem. What was your intention in this contrast?

FredO: That’s an excellent question. One needs to read Langston Hughes several times and ask yourself what is the intent. I put myself in Langston’s shoes as an immigrant composer, and asked, what do I do when walls are put in place to stifle me? When doors of opportunity deliberately shut me out? Do I subject myself to the mental darkness intended for me or do I put on smiling face to shroud the apparent incapacity and soldier on like a warrior? I’d rather you see me smile, as if to say: “evidently, you have put these walls up to keep me out, but I am going to show you that I can eventually break through without satisfying your desire to see me suffer.”

This is a very common defense/survivalist tactic by many oppressed peoples across the globe. They’d rather people not see them suffer; they’d rather be seen to play along, as if to trivialize the hurdles life has dealt them due to society’s avarice. Deep inside, the oppressed populace knows well the severity of walls, overt and covert inhibitions, shattered dreams, etc. I thought of no better medium than Jazz as the appropriate facade to convey Hughes’ poem. However, towards the end of that movement, I totally turned the page, stylistically speaking, so the full impact of Langston Hughes’ poem is meted with great intensity.

The original tradition is very different from the way “Voodoo” is portrayed in Western culture, as a thing of darkness, full of animism and so forth. Vondou or Voodoo is actually more of a way of life – how you live as a community, cooking, birth, marriage, death, a people’s relational metaphysics between the sentient and the unseen worlds.

Yoshi: Tell us about the Vondou oracles you set in the Responsorial section that introduces Michael Castro’s poem, “We Need to Talk,” in Part III, or the final movement.

FredO: The Vondou tradition, the voice of the oracles, comes from the Benin Republic in West Africa, and traveled to places like Haiti, Cuba and other parts of the Caribbean and Latin America. The original tradition is very different from the way “Voodoo” is portrayed in Western culture, as a thing of darkness, full of animism and so forth. Vondou or Voodoo is actually more of a way of life – how you live as a community, cooking, birth, marriage, death, a people’s relational metaphysics between the sentient and the unseen worlds. For this work, I referenced oracles from revered priestesses who surrogated the sage voices of the ancestors.

Yoshi: And they are oracles like Sybils in the Greek tradition?

FredO: Yes exactly, when there are difficulties in the community, like right now in America, these priestesses often become mediums to consult the ancestors for guidance and wisdom. Priestess, or priests or whoever ‘the seer’ is would often go into a trance and assumed the voice of the ancestors. Once in these trances, they’d share what the ancestors are saying about the pertinent issues or difficulty decisions facing a community. Healing messages often are received during these séances. In the olden days oracular messages were memorized and passed on through recitation and praise-singing. In modern times, however, most are written down and there are whole books of these oracles from many cultures where the traditions of divination and libation are still cherished and practiced.

Part III of the work begins with O hadaneh (Please listen). It is an exhortation from the oracles. “Heed my voice; your community is at war. If you don’t listen, you will self destruct” Then in “Listen to the gentle voice,” you have the male members, female members of the community, take turn in echoing the caution of the priestess.

Yoshi: As a member of the chorus learning the piece, I’ve noticed that sometimes you stay close to the structure of the poems, but at other times you have played with them. In the last movement which sets Michael Castro’s poem “We Need to Talk,” you shift the order of some of his lines. I was curious why you chose to do that.

Unfortunately, Dr. Castro passed away December 23, 2018, after a protracted, yet valiant battle with cancer. He was excitedly hoping he could attend the Boston premiere! Thankfully, Adelia Parker-Castro will attend. We also have Mr. Jerred Metz, CEO and Publisher & CEO of Singing Bone Press, to thank for his wholehearted permission to use the poem, “We Need To Talk” from Michael Castro’s last collection, “We Need To Talk.”

Anyway, at that informal MIDI preview in Saint Louis, Missouri, as I read aloud the poem’s text rhythmically to the music, Michael’s eyes grew big with excitement. He said afterwards, “After all, the way we were protesting in St. Louis [during the Ferguson unrest due to the slaying of Michael Brown], it was not a gentle voice, it was a strong voice, by the people. ‘GET OUT of your closed mind!' Wake up and address this bigotry, these injustices!”

Yoshi: Michael Castro was the poet laureate of St. Louis, correct? Were you writing this work very much as a composer from St. Louis?

FredO: Yes, Dr. Michael Castro was the first Poet Laureate of St. Louis. He wrote “We Need to Talk” after those protests in St. Louis, all the images from the uprising, the “riots.” Michael Castro’s poem captures va lot of the things rising in the Ferguson/St. Louis area, things that did not come about overnight, but a frustration that has been brewing for a long time, a community that has been silenced.

Yoshi: What is the relationship between events in Ferguson and elsewhere in the Black Lives Matter movement and this piece?

FredO: Ferguson Missouri unrests mirrored other ‘resistance’ events elsewhere. Michael Castro penned his poem in response to such events. Much progress has transpired among Blacks and other minorities in America. However, we have long ways to go to rid the pervasive injustices and socioeconomical inequality. The way things are now, as a Black man, it doesn’t matter if you are professional, it doesn’t matter how accomplished you are, you have to take two or three looks in your rearview mirror at all times. For Black people, regardless of our economic or social status, the double standards that we are subjected to have caused a lot of pain and frustration in our communities. These frustrations persist, volcanic, and from time to time they burst to the surface, fomenting civil unrest or worse.

These frustrations are not only about race and ethnicity, they are about gender, about walls. They are multi-level frustrations that if left unaddressed will erupt to surface, and disrupt the comforts the privileged in our society have taken for granted.

It used to be that you could drive to the airport anywhere in America, walk to the gate and wave to your friend. After 9/11 all of that changed. We are spending billions for us to be “secure.” These insecurities have become costly. That inconvenience has become the norm, we’ve come to ignore the frustration and accepted this as a norm. Society should not normalize a culture of fear.

I very much dream that someday African Americans will embrace the collective experiences of all African descent peoples in America, and leverage our inherent strengths to further bolster our contributions within this great experiment that is the United States of America. To not do so is to discriminate, to perpetuate a different hue of prejudice or bigotry. Simple.

Yoshi: So this work very much affirms that Black lives matter. Yet in describing it, you identified yourself not just as African American but as “Immigrant composer” which I thought was interesting. Why did you associate that part of your identity with A Triptych of American Voices:

FredO: The phrase “Immigrant composer” is a perfect representation of what I have felt in America since I came over in 1990 and eventually becoming a naturalized citizen in 2000. In the sense that I often face prejudice in two ways. Sometime I swim upstream against the current of injustice from some white Americans – clearly not all. Until people come close to me, I get the usual false stereotypes about African Americans, summarily unaccomplished, economically unadventurous, loafer, etc., and I have to wrestle with them.

And yet sometimes, I, like many other non-American born blacks from Africa and the Caribbean also face injustice from my fellow African Americans. For the most part, black cashiers often would treat me condescendingly once they hear an accent in my speech. Black professionals don’t always see Black people from Africa or the Caribbean the same way, as having the same issues. They see your ‘unusual’ name or hear your accented speech, and they’d subtly think, ah-ha, perhaps you should be my servant! One may have X number of degrees, be accomplished, professionally, but an unusual name or accent can immediately become lame excuse for untoward, prejudiced behavior. This covert prejudice is not often talked about much, but it’s there!

Now when it comes to classical music, there are assumptions and presumptions: “What, you’re from Africa, how come?” I have been here for almost 30 years. I’m among the living African American composers consistently performed around the world, but you'd rarely see my name or works discussed or referenced in professional circles with predominantly African American memberships. In contrast, at the Intercultural Music Initiative (IMI) organization which we founded in St. Louis, when we say we highlight African descent composers, we’ve been deliberately consistent programming works by all black composers – from the United States, the Caribbean and Latin America, Europe and Africa.

I believe the totality of Black heritage should encompass all of Africa descent peoples. I love how Peter Tosh, the late Jamaican reggae icon, puts it in one of his hit-tunes, “African:”

No matter where you come from

As long as you’re black man - you’re an African

No mind your nationality, [No mind you complexion]

You’ve got the identity of an African

I very much dream that someday African Americans will embrace the collective experiences of all African descent peoples in America, and leverage our inherent strengths to further bolster our contributions within this great experiment that is the United States of America. To not do so is to discriminate, to perpetuate a different hue of prejudice or bigotry. Simple.

So I am often in the middle of this crux -- until white Americans get to know me, I am just Black and seemingly by default ‘branded.’ But I’m often having to justify myself to Black Americans, simply because of my accent or unusual name. But, you see, prejudice is not a victimless malady. It also can be a self-inflicting anemia for the perpetrator because of lost opportunities for personal growth.

My relationship with Coro Allegro reminds me of what Viola Davis said when accepting her first Oscar, “There is no shortage of great black artists. All we need is an opportunity.” That is what Coro Allegro and David Hodgkins gave me: an opportunity.

Yoshi: What does it meant to be writing this extraordinary work for Coro Allegro, Boston’s LGBTQ+ and allied classical chorus to premiere?

FredO: Initial credit goes to our mutual friend, Darryl Hollister [Coro Allegro’s beloved accompanist since 1993 and winner of the 2019 Daniel Pinkham Award for his work championing African and African American composers]. My wife Wendy Hymes, a flutist, says, “There are few pianists with the pedigree of Darryl Hollister as a musician. Though for reasons of clarification, Darryl is African American, Darryl defies definition or any kind of limiting demographic labels. We both know him as one of those perfect human beings that you rarely meet. He is color blind; he is artistically neutral.” I still dream of a paradigm shift where an artist of Darryl Hollister’s caliber is featured and celebrated on some of the finest concert stages of the world. It’s not too late, is it?

Our musical collaborations since 1998 gave him the confidence to introduce me to David Hodgkins and Coro Allegro. When Maestro Hodgkins first heard that piece [Onovwerosuoke’s “Caprice for Piano and Orchestra,” premiered by Coro Allegro in 2017], he was totally shocked, As he later put it, he didn’t know how to express or what words to describe what he had heard.

My relationship with Coro Allegro reminds me of what Viola Davis said when accepting her first Oscar, “There is no shortage of great black artists. All we need is an opportunity.” That is what Coro Allegro and David Hodgkins gave me: an opportunity.

Yoshi Campbell sings and writes about music for Coro Allegro, Boston’s LGBTQ+ and allied classical chorus, and serves on the Steering Committee for the Network of Arts Administrators of Color of ArtsBoston (NAAC Boston).